'She grinds her colours, escapes an age of limits'

Jacqueline Saphra's Veritas: Poems after Artemisia and The Nine Mothers of Heimdallr by Miriam Nash, are both published by Hercules Editions. Richard Price admires the layered skill and care that from which these books have been created.

VERITAS -- There are so many doors this beautifully produced book opens: the paintings of the seventeenth century artist Artemisia Gentileschi feelingly and expertly commented upon by Saphra via the poems and her afterword; the struggles and achievements of women then and now; the sheer artistry of the poems and the architecture of the final sonnet, containing a line from each of the preceding ones, bringing the crown of sonnets together; the lovingly reproduced paintings themselves; and the art historical context accessibly introduced by Jordana Pomeroy. “She grinds her colours, escapes an age of limits” – what a brilliant line, summarising the labour and the talent, and that leap up: it captures the energy and achievement of this book.

So it is certainly a beautiful book, a very informative book, and a clever book. Even so, the reader shouldn't miss, amid the high production values and technical accomplishment something much angrier; unreconciled. There is, rightly, a very steely critique running through all these poems. Gentileschi was raped early on in her life and, even though her attacker was - almost incredibly, given the prejudices of the time - found guilty, she suffered a severe loss of reputation. The 'age of limits' was not 'just' artistic but existentially suffocating for women, and this book is a sustained commentary on Gentileschi's subtle even sly approach to that warped, vicious world commodified and made desirable by men's control of art: 'She offers up her truth, immortalised / to please the patrons, art in her hands, as if / she's soft enough for men to idolise."

At a technical level, Saphra doesn't only manage the demands of the crown form, passing on one sonnet's last line to be repeated in the first line of the next, and the accumulation of all first lines in the final sonnet, she keys each opening line to the topic of the accompanying painting. Bearing in mind that this therefore becomes a three-dimensional constraint, this is a remarkable feat. But it feels fluid. For example there is a sense that Gentileschi changes over time - "Truth costs; deference is cheap" is a phrase in a later poem- and that such change may have altered not just the subject of the painting but actual technique, a shallower application of paint: "My brush moves across the surface of the deep." The 'Veritas' of the title is at times necessarily a private truth - "she hides her longings in the violet shadows" - and what was certainly a life that fought and won a personal triumph, was, Saphra reminds us, only a rarity, and far from a perfect victory.

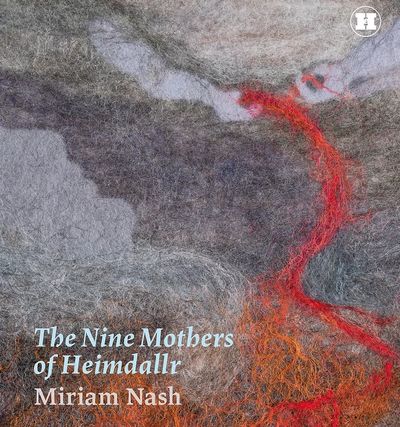

The Nine Mothers of Heimdallr by Miriam Nash, again from Hercules, also has clear feminist concerns and is as lovingly produced in poetry, context (by authority Jóhanna Katrín Friðriksdóttir), and image.

Nash has gone back behind the better-known Norse gods such as Thor and Odin to their Titan-like female predecessors, creating a ballad of female community and power which is part creation myth, part tragedy, even part lullaby. Female presence is strong but even so love proves fluid and so gender does.

The poem is as intimate as a parent gently explaining a child’s back history to them, using shapes in the fire to ‘see’ the characters, a key metaphor for the imagination. It is implied that the child has heard this tale before, so there is the affection of a knowingly shared experience. But the poem is mercurial - yes, intimate, but 'big' -- there's a ballad and public aspect to it, as well, and this is one of its interests.

The poem is as heroic as a bard explaining the story to an audience in a large hall, and creation myths are woven in to what becomes, beneath a deceptively simple approach, a poem layered with complexities of different kinds of distance, tonally and technically: recovery of far-off female gods, recovery of peace in a war-obsessed world, recovery of reliable privacy in a world of public ‘heroics’. In a touch entirely in keeping with the theme, warm, textured fabric-pictures are provided by Nash’s mother the artist Christina Edlund-Plater and mother and daughter interview each other in a feature at the end.

Though their approach is almost diametric, Hercules Editions are particularly good at the City Lights style pocketbook format of the book and both these volumes are in that form. City Lights ‘go on their nerve’ in O’Hara’s phrase, beat-style – Hercules are careful, researched, formally traditional – but both, in their own very different ways, are beautiful and contemporary to their time. These really are books that will fit easily in a pocket or handbag. So handsome are they rendered, one would not want them to languish there for long: when cafes, pubs, and public transport are safe again, they are for reading very publicly, flaunting in fact.

About Richard Price

He edits this site. He is the author of The Owner of the Sea (Carcanet), new poems rendering three extraordinary Inuit myths in 'real time'. And two collections of the year: Small World (Creative Scotland Poetry Book of the Year) and Moon for Sale (A Guardian Book of the Year, chosen by Carol Rumens).